|

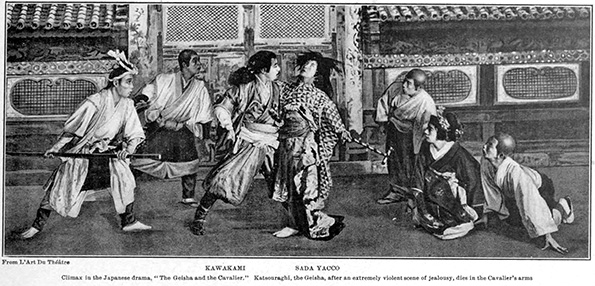

| From L'Art Du

Théatre

KAWAKAMI SADA YACCO Climax in the Japanese drama, "The Geisha and the Cavalier." Katsouraghi, the Geisha, after an extremely violent scene of jealousy, dies in the Cavalier's arms. |

Theatres and Theatre-Going in Japan

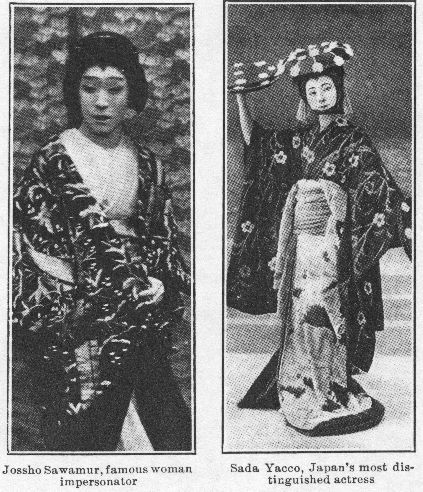

MODERN Japan, despite its ready adoption

of Western manners, is in things theatrical still faithful to the ancient feudal

days, and the sanguinary, interminable dramas written many centuries ago are

still the chief attractions in the Mikado's theatres. It is true that within the

last few years—in fact, since the triumphant European and American tours of

those distinguished Japanese players, Sada Yacco and Oto Kawakami—the old

school drama has to some extent lost ground, and quite recently performances of

Shakespeare's "Othello" and "Hamlet," and Daudet's "Sappho" have been received

with favor by Tokio audiences.

MODERN Japan, despite its ready adoption

of Western manners, is in things theatrical still faithful to the ancient feudal

days, and the sanguinary, interminable dramas written many centuries ago are

still the chief attractions in the Mikado's theatres. It is true that within the

last few years—in fact, since the triumphant European and American tours of

those distinguished Japanese players, Sada Yacco and Oto Kawakami—the old

school drama has to some extent lost ground, and quite recently performances of

Shakespeare's "Othello" and "Hamlet," and Daudet's "Sappho" have been received

with favor by Tokio audiences.

The explanation of this curious survival of the old form of play, at a time when all Japan is eagerly imitating the foreigner, is undoubtedly to be found in the peculiar customs of the country. The progressive Japanese finds it easier to change his mode of dress than to reform habits bred in the bone. The old plays, lasting, as they formerly did, from early morning until nearly midnight, just suited the Japanese play-goer, who, when he does go to the theatre, makes an all-day affair of it. Indeed, theatre-going in Japan is a very serious matter, like an ocean voyage or long railroad journey with the American, and not to be entered upon lightly or without due preparation. Some ten or twelve years ago the Japanese police limited the duration of a dramatic performance to eight hours, and more recently Sada Yacco and Oto Kawakami, who learned a good deal in their foreign travels, introduced the comparatively short evening performance of three or four hours, an innovation which was at once welcomed by the better class of people. But the new arrangement found little favor with the general public, whose honorable traditions it rudely upset, and particular indignation was aroused in the bosom of the Japanese Matinee Girl—fully as important a person in Japan as in America—who loves to sit in the theatre as long as possible and weep over the play. For, to the gentle mousmé, the theatre is essentially the place for weeping. Japanese girls are extremely sentimental, and a play without borrowing situations would not appeal to them in the least. The musical comedy—as presented in America and England—is quite unknown in Japan, for which we Japanese should perhaps be devoutly thankful. Recently, attempts have been made to introduce grand opera in the Flowery Kingdom, but only with indifferent success.

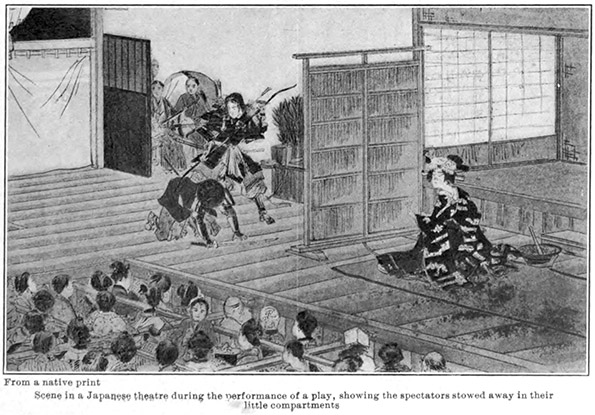

From a native print. Scene in a

Japanese theatre during the performance of a play, showing the spectators stowed away in their little compartments.

Three kinds of plays are popular in Japan—the religious dramas, mingled with

farce, the domestic dramas of everyday life and love, and the historic dramas,

bristling with blood and suicides, which are liked best of all. The religious

drama dates from the ninth century, when the country was visited by a terrible

earthquake. Flames issued from the ground, and the priests, to propitiate the

gods, executed [<167] a dance near the spot. The flames at once stopped, and in

recognition of the miracle every performance of a religions play to this day is

preceded by the Sambash or rhythmic dance executed by an old priest and

accompanied by a plaintive chorus.

The

programme for one day usually consists of three different pieces. The first is

invariably an historical play, dealing with some noble family—its quarrels and

misfortunes; and the third is a love story. The piece between these two is

called a "Middle Curtain," being a classic with a wonderful display of dress and

dancing.

At the end of each act the curtain is drawn to slowly in order to let the spectators remain as long as possible under the spell of the situation, which is continued, but at the end of the intermission it falls abruptly in order to dazzle the public suddenly with the splendor of the picture. These drop curtains are covered with enormous characters and in striking colors: black on orange, white on blue, violet on red. The same curtain is not used during the whole performance. It is the custom to make the present of a curtain to a favorite actor. Thus, when speaking of a popular performer, you say, "He has so many curtains!"

|

|

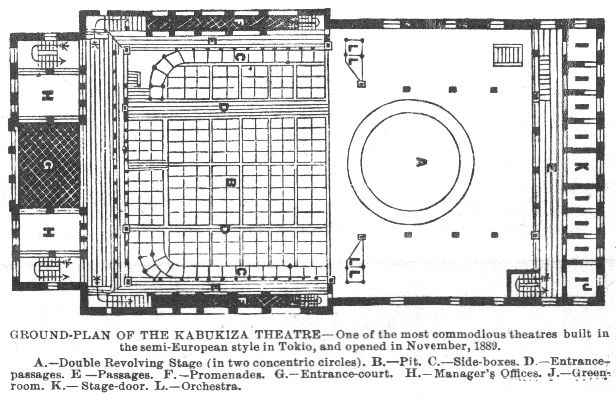

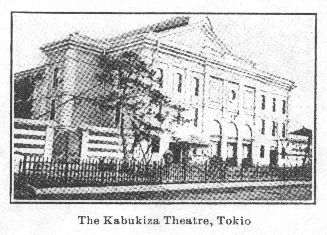

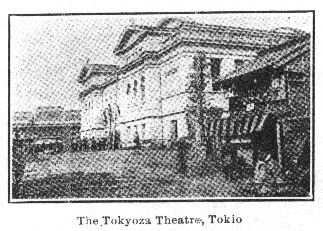

There are several fine theatres in Tokio, the most

important being the Kabukiza, the Meijiza, and the Tokyoza. They are

imposing edifices constructed of stone in semi-European style, but the

interior is arranged in the old Japanese manner which has been in vogue

since the birth of the native drama. You do not purchase your ticket at the

box-office, as in other countries, but at the neighboring tea-house, where

arrangements are also made to keep your party supplied with refreshments

during the long hours the play lasts. Over the main entrance of the theatre

is a large framed poster depicting scenes in the play then being performed.

Entering the theatre you see a large square floor partitioned off into tiny

compartments or boxes, giving the effect of a gigantic checker board. The

boxes are three feet square by about three feet high, and they each

accommodate four or five persons. On either side of the parterre, and almost

level with the top of the boxes, is a plank which runs from the entrance

down to the stage. This is called The Flower Path, its sides in olden times

having been decorated with flowers. The Japanese stage is always supposed to

face the south, but the origin of this tradition has been lost in time.

There are two or three rows of boxes outside the flower path, raised

slightly higher than the parterre, and the auditorium is closed on both

sides by other boxes. On the second floor, facing the stage, are similar

boxes, rising one behind the other and closed in at the back by a long,

barred window. On the far side of this window is a narrow passageway or

"chicken coop" to which are admitted those theatre-goers who on payment of

two cents can see a single act. These form a special public, and a most

important one to the Japanese manager. They are theatre enthusiasts who

cannot let a day go by without seeing at least some part of the play. They

are known as the success makers. They are equally well known as the noise

makers! The din they make whenever one of their favorite actors makes his

entrance is appalling. They shout Naritaya! (the stage name of the

late celebrated Danjuro). The success or failure of a performance depends on

the amount of noise they succeed in making, for in Japan very little

attention is paid to what the dramatic critics have to say. Happy land!

There are several fine theatres in Tokio, the most

important being the Kabukiza, the Meijiza, and the Tokyoza. They are

imposing edifices constructed of stone in semi-European style, but the

interior is arranged in the old Japanese manner which has been in vogue

since the birth of the native drama. You do not purchase your ticket at the

box-office, as in other countries, but at the neighboring tea-house, where

arrangements are also made to keep your party supplied with refreshments

during the long hours the play lasts. Over the main entrance of the theatre

is a large framed poster depicting scenes in the play then being performed.

Entering the theatre you see a large square floor partitioned off into tiny

compartments or boxes, giving the effect of a gigantic checker board. The

boxes are three feet square by about three feet high, and they each

accommodate four or five persons. On either side of the parterre, and almost

level with the top of the boxes, is a plank which runs from the entrance

down to the stage. This is called The Flower Path, its sides in olden times

having been decorated with flowers. The Japanese stage is always supposed to

face the south, but the origin of this tradition has been lost in time.

There are two or three rows of boxes outside the flower path, raised

slightly higher than the parterre, and the auditorium is closed on both

sides by other boxes. On the second floor, facing the stage, are similar

boxes, rising one behind the other and closed in at the back by a long,

barred window. On the far side of this window is a narrow passageway or

"chicken coop" to which are admitted those theatre-goers who on payment of

two cents can see a single act. These form a special public, and a most

important one to the Japanese manager. They are theatre enthusiasts who

cannot let a day go by without seeing at least some part of the play. They

are known as the success makers. They are equally well known as the noise

makers! The din they make whenever one of their favorite actors makes his

entrance is appalling. They shout Naritaya! (the stage name of the

late celebrated Danjuro). The success or failure of a performance depends on

the amount of noise they succeed in making, for in Japan very little

attention is paid to what the dramatic critics have to say. Happy land!

When a Japanese makes up his mind to go to the theatre, he proceeds first by

interesting his neighbors. If he is a married man he consults his wife and

daughters. If he is a bachelor, he gets together a party of friends. The

Japanese women are passionately devoted to the drama. It is usual for a party to

book a box through a tea house connected with the theatre and at the same time

make arrangements for what refreshments they wish served. The Japanese maiden

makes the most elaborate preparations days beforehand, and when the eve of the

eventful day arrives, she has been known to sit up all night so as not to

oversleep herself the next morning. To be at the theatre on time, playgoers must

rise with the sun, and all their meals, including breakfast, are eaten in the

tiny box in the playhouse. It is not an easy task to reach one's seats and once

the family has settled down, nothing but a catastrophe would induce it to leave

its box. They eat in it, smoke in it, nurse babies in it, and put themselves

thoroughly at their ease. In each box there is a small stove, at which they

light the short Japanese pipe, and at their side is the plate of rice and fish

with the traditional chop sticks, and a bottle of saka (rice brandy) and

cups of tea, which are filled as often as emptied. The women chew candy and the

men partake freely of saka as the play goes on. A man who has been

obliged to escort his women relatives is often to be seen fast asleep, for

politeness to women is not seriously discussed in Japan. During the

intermissions, attendants with cakes, confectionery and tea pass up and down the

elevated aisles offering their wares.

When a Japanese makes up his mind to go to the theatre, he proceeds first by

interesting his neighbors. If he is a married man he consults his wife and

daughters. If he is a bachelor, he gets together a party of friends. The

Japanese women are passionately devoted to the drama. It is usual for a party to

book a box through a tea house connected with the theatre and at the same time

make arrangements for what refreshments they wish served. The Japanese maiden

makes the most elaborate preparations days beforehand, and when the eve of the

eventful day arrives, she has been known to sit up all night so as not to

oversleep herself the next morning. To be at the theatre on time, playgoers must

rise with the sun, and all their meals, including breakfast, are eaten in the

tiny box in the playhouse. It is not an easy task to reach one's seats and once

the family has settled down, nothing but a catastrophe would induce it to leave

its box. They eat in it, smoke in it, nurse babies in it, and put themselves

thoroughly at their ease. In each box there is a small stove, at which they

light the short Japanese pipe, and at their side is the plate of rice and fish

with the traditional chop sticks, and a bottle of saka (rice brandy) and

cups of tea, which are filled as often as emptied. The women chew candy and the

men partake freely of saka as the play goes on. A man who has been

obliged to escort his women relatives is often to be seen fast asleep, for

politeness to women is not seriously discussed in Japan. During the

intermissions, attendants with cakes, confectionery and tea pass up and down the

elevated aisles offering their wares.

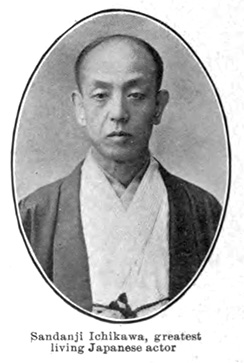

The Japanese thespian is a vastly more important

personage than his professional brother in other countries.

Directly he makes his appearance on the plank leading to the

stage there is a flutter of excitement among the audience,

and fans, purses and tobacco pouches, which have been

specially embroidered for him, are thrown to him. When he

reaches his dressing room lie finds notes containing burning

declarations, and his effigy adorns the tortoise-shell

hair-pin that keeps up the raven tresses of many a dainty mousmé. But the player has a more substantial reward

than mere social success. He is also well paid. The Japanese

theatrical season only lasts four or five weeks, but a good

actor in that time can easily make his $5,000, while the

wretched playwright, a poor, despised creature who in Japan

is looked upon in the light of a theatre attaché, has to be

satisfied with a miserly $100. When a manager wants a new

attraction, he sends for the official playwright and

suggests a subject. The author prepares two or three

scenarios, of which the manager selects the best, and then

the actors also have the right to alter the plan, to suit

themselves.

The Japanese thespian is a vastly more important

personage than his professional brother in other countries.

Directly he makes his appearance on the plank leading to the

stage there is a flutter of excitement among the audience,

and fans, purses and tobacco pouches, which have been

specially embroidered for him, are thrown to him. When he

reaches his dressing room lie finds notes containing burning

declarations, and his effigy adorns the tortoise-shell

hair-pin that keeps up the raven tresses of many a dainty mousmé. But the player has a more substantial reward

than mere social success. He is also well paid. The Japanese

theatrical season only lasts four or five weeks, but a good

actor in that time can easily make his $5,000, while the

wretched playwright, a poor, despised creature who in Japan

is looked upon in the light of a theatre attaché, has to be

satisfied with a miserly $100. When a manager wants a new

attraction, he sends for the official playwright and

suggests a subject. The author prepares two or three

scenarios, of which the manager selects the best, and then

the actors also have the right to alter the plan, to suit

themselves.

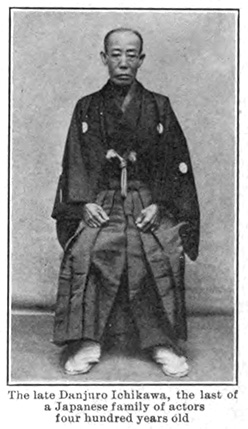

Japanese audiences are very loyal to their favorites. What enthusiasm there used to be when the great Danjuro made his appearance! This magnificent actor, the greatest tragedian ever known in Japan, died a few months ago. He left no son, and it is a question who will inherit his name, which has been prominently connected with the Japanese stage for nearly four hundred years! And how delighted we were to watch the late Kikugoro, that wonderful actor whose talented son Baiko is now a matinee idol.

In 1890 the realistic acting of Oto Kawakami and Sada Yacco appeared as a protest against the old school. They were encouraged by the intelligent public, and they put on the stage an adaptation of "Sechu Bai," a political novel. This was the first time that a novel had been dramatized in Japan. With the death of its two greatest actors, Danjuro and Kikugoro, the old school of Japanese drama is declining. The past régime is slowly but surely merging into the new, only following in this, the irresistible progressive movement to which modern Japan owes her present important place among the nations.